Java was first releases in 1996. After almost 30 years and more than 20 successive iterations of the

language, it comes to no surprise that it has a few dusty corners and surprising quirks. One of them

is the difference between == and .equals. If you come from more modern languages, such as Go,

you might expect that new MyClass("a") == new MyClass("a")… but it is not the case!

Reference equals (==)

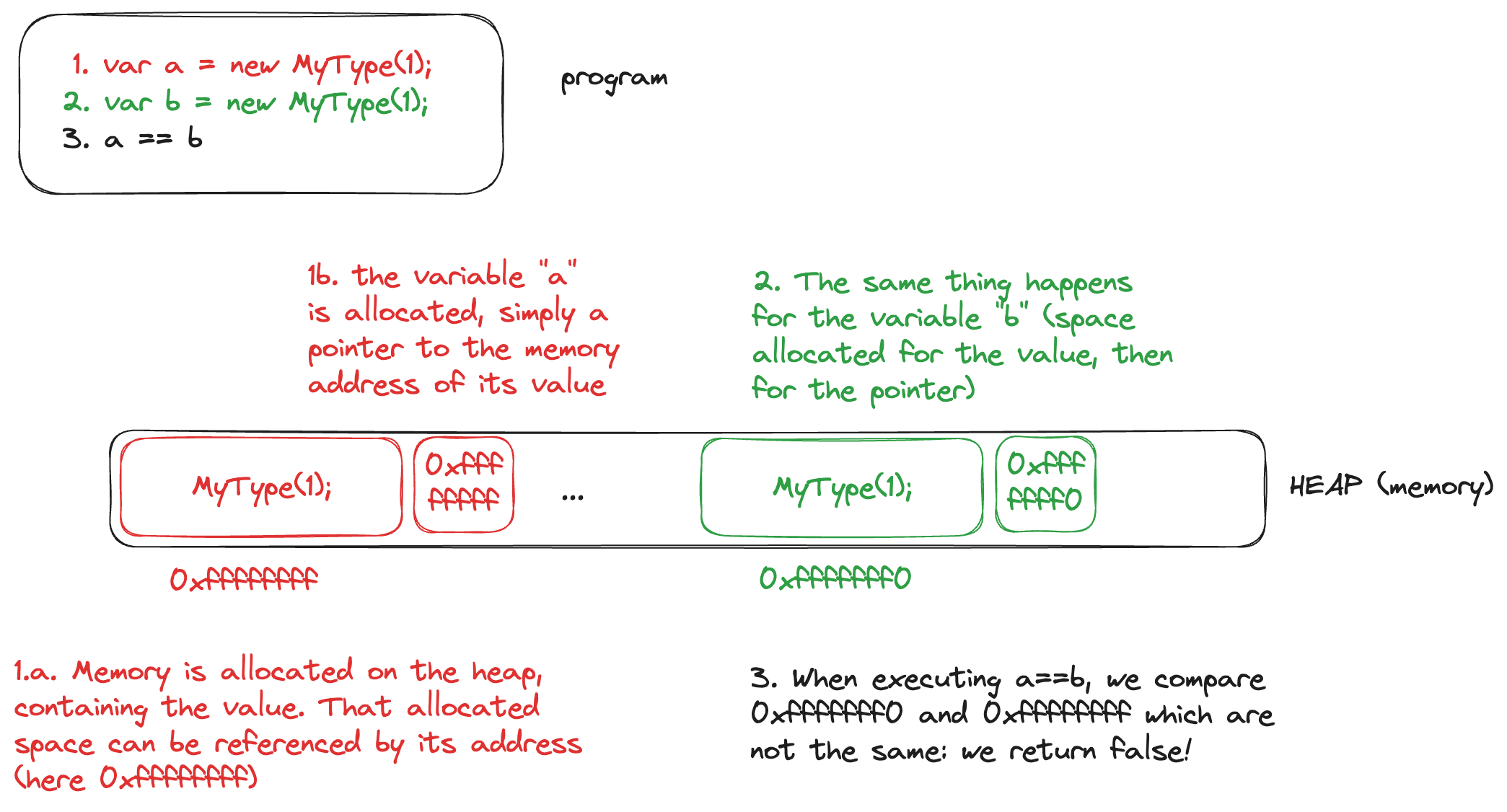

In Java == operates on references. This means that a == b will return true if and only if

both a and b point to the exact same object in memory. So, for example:

jshell> record MyType(int a) {}

| created record MyType

jshell> var a = new MyType(1)

a ==> MyType[a=1]

jshell> var b = new MyType(1)

b ==> MyType[a=1]

jshell> a == b

$5 ==> false

Here, while a and b have the same value, they point to two different objects so == returns

false. While this is not a perfectly accurate representation of what happens in memory, you can

imagine it so:

The equals method

In Java, java.lang.Object is a class, and is the root of the entire class hierarchy. This means

that every single class implicitly has extends Object even if it is not stated in the code.

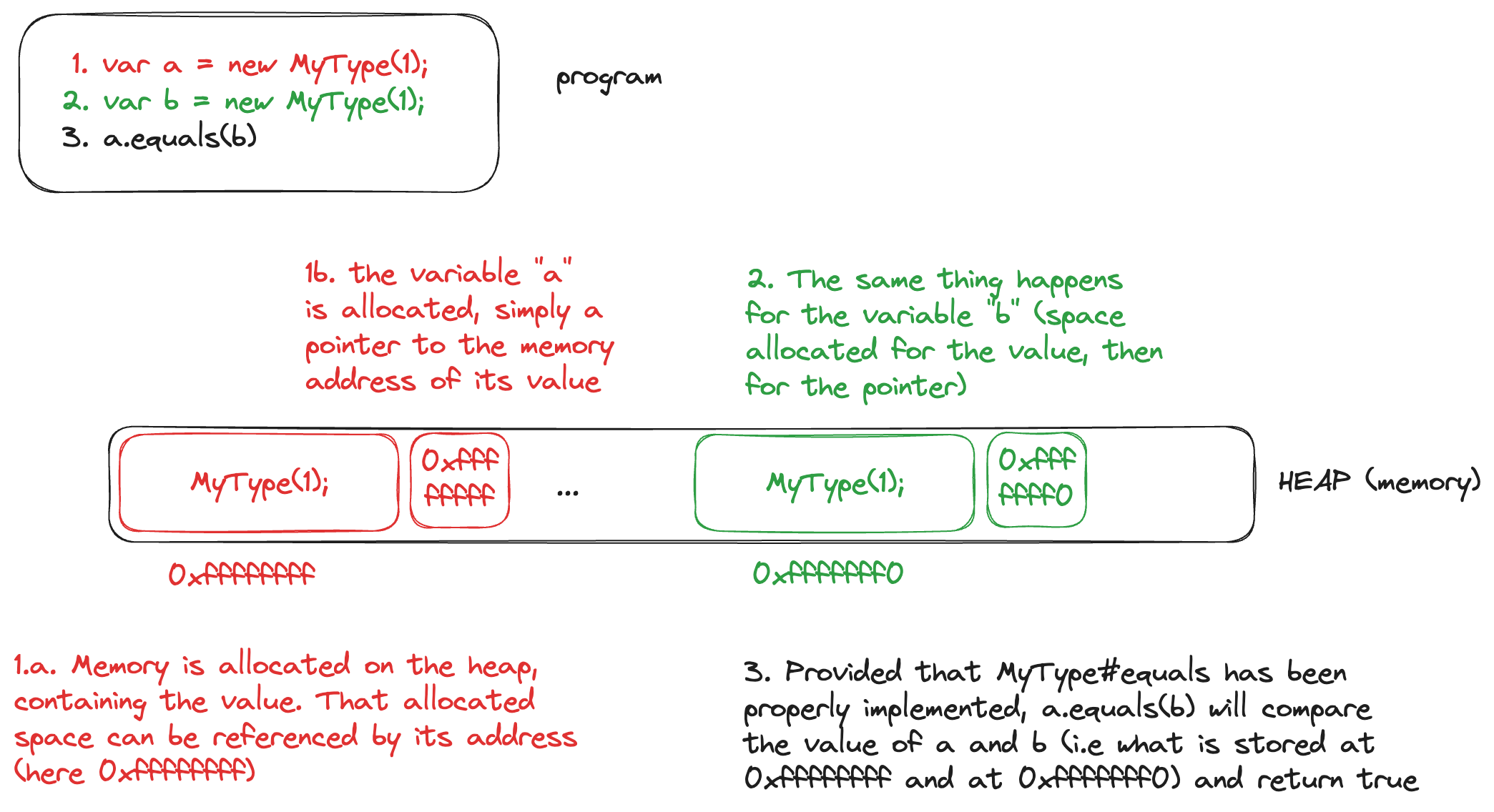

Object defines an equals

method

that is therefore available on every single class. By default, this method uses the reference

equals. The big difference is that, being a method, you can override equals. And this is where you

can specify a behavior that compares the value instead of the reference. For example, the

default implementation of equals in records compares each field individually and returns true if

and only if fields are equal according to their respective equals method (or if they are both

null).

You can imagine it like this:

You may wonder, what if these fields are objects themselves? Won’t we end up calling equals all

the way down until we reach a class like Object that just uses the reference equals (==)? And

this is where we should talk about boxed types and primitive types.

Primitive and boxed types

Java distinguishes two types of types:

- primitive types

- object types

Primitive types are special in the sense that variables of a primitive type are not pointers to a

memory address. Instead, their value is directly stored on the heap when they are declared. This

means that two primitive values cannot share a value stored at the same place in memory… and

also that a == b will actually compare values when operating on primitive values! This is why the

following work “as expected”:

jshell> 1 == 1

$6 ==> true

jshell> 3.2 == 3.2

$7 ==> true

jshell> true == false

$8 ==> false

There are 8 primitive types in java: byte, short, int, long, float, double, boolean

and char. That’s it! Everything else is an object, and uses references.

The case of strings and enums

You might have noticed that strings are not primitive types. In fact, when you write var a = "abcd", you are using syntactic sugar: the compiler will transform it to var a = new String("abcd") for you. String is a subclass of Object, like any other class, and thus has an

equals method implemented for you. This is why you see the following:

jshell> var a = "abc"

a ==> "abc"

jshell> var b = "ab"

b ==> "ab"

jshell> var c = "c"

c ==> "c"

jshell> b+c

$19 ==> "abc"

jshell> a == b + c

$20 ==> false

jshell> a.equals(b+c)

$21 ==> true

What about enum then?

enum MyEnum {

A, B;

}

Since values of type MyEnum are necessarily A or B (you cannot do new MyEnum("A")!), then

using .equals or == is the same thing (both values of type MyEnum either have the same value

AND the same reference, or they have different values AND different references).

Conclusion

In Java, except if you are dealing with primitive types (or enums), you should always use equals,

unless reference comparison is what you’re looking for.